“There is a momentous, broad-based cultural shift underway that has struck at the roots of every industrialized system of education. The result is a demand for more personalized learning, brain-friendly environments, less recall and more thoughtful application of knowledge, optimal conditions for eliciting intelligent behaviors, constructivist tools, and respectful, caring relationships that honor the learner.” — Thom Markham

The impetus for the cultural shift that Markham describes in

Redefining Smart: Awakening Students’ Power to Reimagine Their World is well-documented. The wide-ranging dialogue concerning this new reality — a radically different conception of learning — is no longer a debate. Part of the complexity for schools seeking to address this challenge includes the obligation to make the transition without unduly alarming those who assess the quality of schooling through a lens traditionally known as rigor.

There are many misconceptions that govern the worldview of rigor in education. At its most fundamental level, advocates of rigor believe that school should be “hard”. Rigor is most frequently characterised by an abundance of homework, tests, grading, and compliance. In a school that is “hard” some students will be successful, while others will not. The notion of a learner-centred school context might be new to many of us educated in the 20th century. For parents, there are only the familiar elements of their own school experiences to relate to. The paradigm shift that can be dramatic for professional educators must be incredibly daunting for parents who note a fundamental shift in the way we think about learning. According to Markham: “Instead of measuring difficulty in terms of information retrieval, or amount of homework, the new standard of personal rigor puts thinking and intelligent behaviors at the forefront. How a student expresses those personal qualities become the standard for capability and performance. In effect, we’re starting to redefine what is ‘hard’ in school.”

So what happens when a school takes the shifting digital landscape seriously, acknowledging how the brain works, the essential need for intrinsic motivation, the reality of the declining value of fixed knowledge, the importance of social and emotional learning, and the critical need to focus on learning how to learn in new and dynamic ways? What must proponents of traditional rigor think when their child attends a school that:

Does not grade homework or believe in assigning it unless it serves a clear learning purpose.

Believes that averaging grades is illogical and allows students to negotiate assignment deadlines.

Eliminates streaming to increase challenge while believing that every student can succeed.

Regards the development of a digital presence and personal learning as educational priorities.

Is committed to the arts, design, creative expression and physical education as core curriculum.

“The chief barrier to moving forward is an outdated definition of rigor. The core task of the modern world is not to prep students for standardized tests by delivering content, or even to make them “college ready,” but to prepare them to judge the quality of information, generate new ideas, filter them through a net of critical analysis and reflection, and share and move the ideas through a design process to create a quality product, either as an idea or a material object.

Much of the above, for some, represents a lowering of standards, a dilution of rigor. The reality of where we have come from and where we need to go is clear, but the pursuit of this direction is not without its challenges. “It is indisputable that a set of industrial beliefs are ingrained in the mental model we call education… Moving from the quantifiable apparatus of schooling to the qualitative expressions of deeper intelligence — and to more personal, individual standards for thinking and accomplishment — is a huge thought barrier to cross. Welcome to 21st century life.”

Of course, it is not acceptable for schools to declare that rigor is a thing of the past, that new approaches to learning should not be open to scrutiny or that a commitment to excellence has become less important than in the past. What is required is a new definition of rigor and a commitment to educating all stakeholders in understanding why learning has changed and how schools need to change accordingly. This process will take time, patience, strong leadership and an acknowledgment that not everyone will accept the need for change or applaud the implementation of transformations that unsettle the core of traditional certainty. But continuing to do what we have always done does not honour our obligation to students and the realities of our interconnected, digital world. As Markham points out:

The task of redefining rigor is an important one. I like the new definition that Brian Sztabnik has set forth: “Rigor is the result of work that challenges students’ thinking in new and interesting ways. It occurs when they are encouraged toward a sophisticated understanding of fundamental ideas and are driven by curiosity to discover what they don’t know.” This definition is notable in that it makes no reference to getting into the “best” college.

I was fortunate to enjoy a screening of the film “Most Likely to Succeed” at the

CoSN Conference in Washington DC recently and to hear the perspective of executive producer, Ted Dintersmith. I highly recommend that schools

make arrangements for a screening of this important film. There is one scene in the film that especially resonated with me. In this scene, a teacher at High School Tech in San Diego, (who is using modern learning strategies with his students), holds a meeting with some of his “stronger” students who appear disgruntled with these methods. To paraphrase the exchange, he asks these students whether they would like to be equipped to lead meaningful lives or to ace the test. The shared perspective that the test results were more crucial than learning how to live meaningfully — that the development of personal interests and passions could wait — speaks volumes about the cultural expectations around schooling these days.

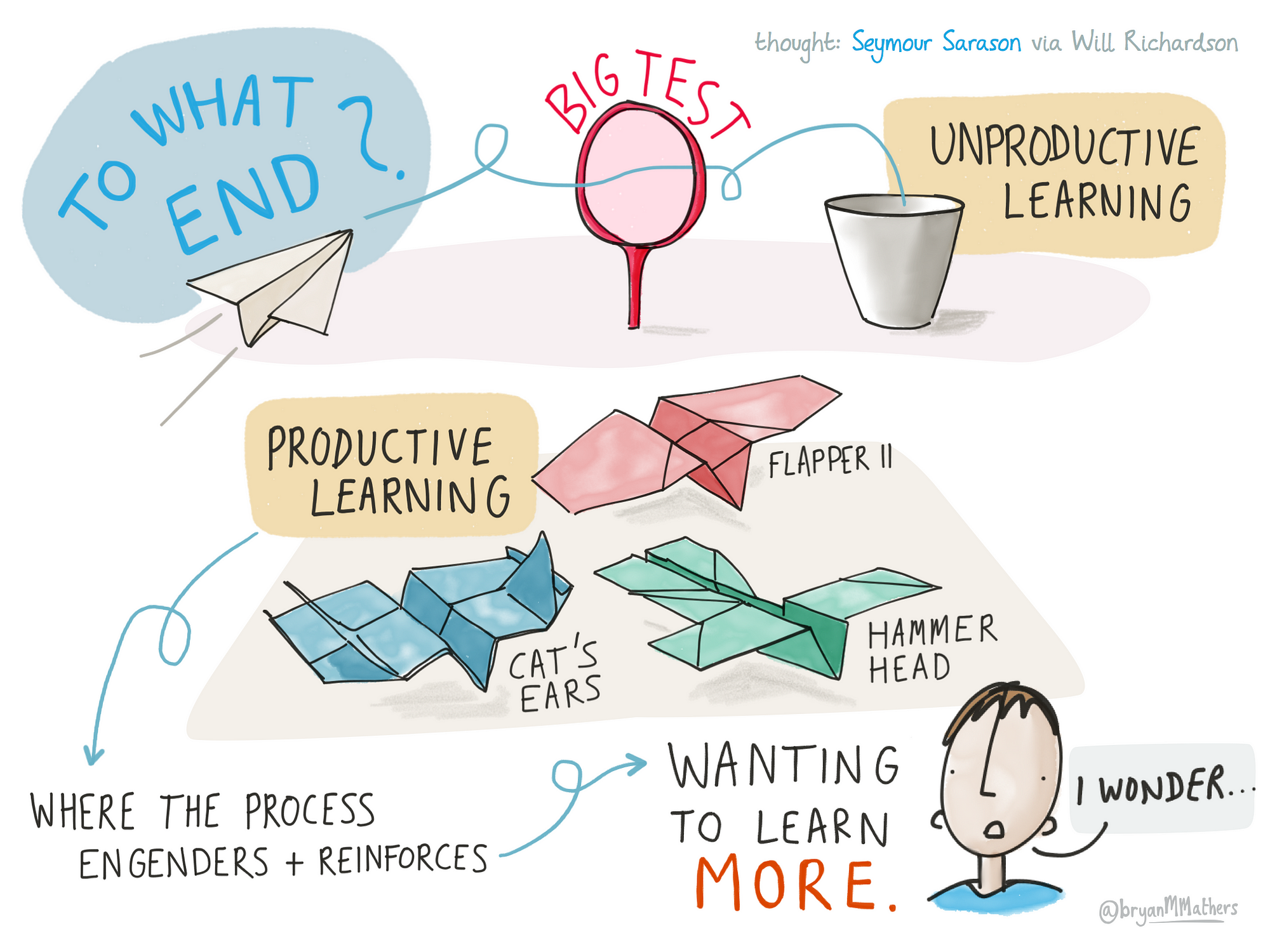

The real essence of rigor is doing the right thing for students and ensuring they have the most dedicated, personally invested teachers to guide, mentor, coach and support them. We must have rigor in schools, but in a new context. Modern learning needs to be productive and have purpose. That purpose is related to the real world, not the game of school, long the domain of traditional rigor. While learning will inevitably look different in this new context, the core essence of the relationship between engaged students and caring teachers has never been more important.

Eric Sheninger, in his new book, deals with the issue of rigor in some practical ways that are the hallmark of his writing. He suggests that teachers in the contemporary digital landscape need to take care to consider whether modern methodologies are still as structured, rigorous, and relevant as before. For Sheninger, the critical instructional design questions modern teachers need to ask include: “What capabilities do I want my students to develop? In what specific ways is my instructional design rigorous, relevant, and goal oriented? What are my benchmarks for rigor? Relevance? Relationships? Clear objectives?”

Engagement and personal meaning are the new rigor. Digital learning, balanced with traditional, challenging expectations deepen, rather than dilute rigor. Parents and educators are right when they suggest school needs to be rigorous. But if we accept — as we must — that the needs of the first half of the 21st century are inevitably and distinctly different from the second half of the 20th century, what this rigor looks like needs to be reconsidered and embraced with the modern mindset required. Nothing less than a rigorous commitment to this paradigm shift will prepare our young people for the futures they deserve.

References